Road Relevant - F1 Technology

The new regulations have turned the F1 circus upside down in an effort to bring these single-seater racers closer to streetcars. But, has it worked?

The new regulations have turned the F1 circus upside down in an effort to bring these single-seater racers closer to streetcars. But, has it worked? Well, several experts are convinced that the solutions developed for F1 will find a place in our cars of tomorrow.

How will F1 fare in 2014? According to the reaction after the first few races, its popularity index appears to be dropping. But, from a more technical perspective, there’s no shortage of ideas according to F1 insiders. The FIA’s attempt to make F1 cars more road relevant seems to have unanimous approval from the engineers.

Useful Simulations

As confirmed by Gian Paolo Dallara – ‘father’ of several single-seaters that play a leading role on race tracks the world over, from GP2 to Indycar – race cars of the past were thought of exclusively for racing purposes. Nowadays, however, the emphasis is on energy saving engines and power recovery while braking. The new F1 regulations dictate a very specific ratio based on low consumption and high performance – leading to solutions the likes of which we’re likely to see on top class road cars in the near future.

Besides the power units, there are other relevant aspects to the regulations as well. The prescribed regulatory equivalence between the time spent in the wind tunnel and the time devoted to Cfd (computational fluid dynamic) provides strong emphasis on the latter – and this will prove to be an advantage for the design and planning of road cars in future. But, is Dallara’s opinion an isolated voice? Not at all! Another influential expert and motorsport representative is Mauro Forghieri, and he shares the same point of view.

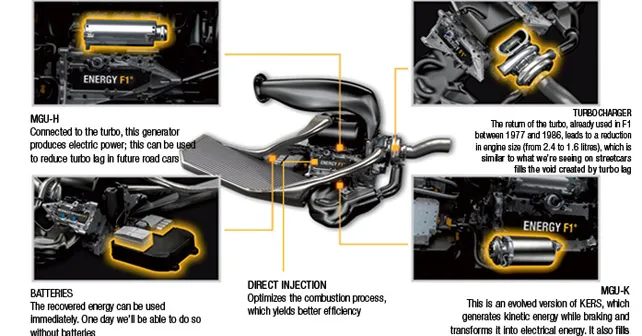

“I strongly support the choice made by the FIA, since it’s in line with what more-and-more car manufacturers are doing with respect to downsizing – i.e. fitting smaller sized turbocharged engines that produce as much power as before, but consumer less fuel and produce fewer emissions.” Furthermore, Mr. Forghieri reminds us that “if we analyse the efficiency of current thermal engines, we arrive at a value of just 30%. If we perform an even more elaborate well-to-wheel calculation that figure drops to just 5%.” But, he also points out that the innovations are interesting, as they allow us to develop a remedy for the Achilles heel of the turbocharger – turbo lag. Forghieri explains, “The electric motor enhances the modulation of power supply according to the drivers’ needs. The power generated by the batteries make the turbine spin even during the release phase, so that power is available whenever the driver asks for it.”

All is well then? Not really. Since there is an aspect that doesn’t convince the engineers much – the presence, imposed by the FIA, of a flux controller, which ensures that fuel capacity cannot exceed 100kgs per hour.” Mr. Forghieri has some doubts, “It was not needed. Why prevent a driver from consuming more petrol in the first phase of a race, and then controlling the pace?” The same opinion is shared by Enrico Benzing, engineer and senior F1 journalist, “ Why was the FIA in such a rush? More efficient turbocharged engines are fair enough, along with energy saving measures. But the changes should have been gradual – 1.6 litre turbocharged engines matched with a KERS system with twice the power of the previous system would have been enough of a step ahead.” Benzing agrees with Dallara that the power units – with their high pressure injectors, developed by Magnetti Marelli – are the way forward.

A flood of ideas

The atmosphere is extremely positive and euphoric at the headquarters of this Italian company. After several years of ‘frozen’ engines, we’re back to talk of new technological challenges. And the trademark of the Fiat-Chrysler group is very much present in the current world of F1 – as it supplies engine components and parts of the hybrid system to Ferrari, as well as some elements of the latter and engine control units to Renault, plus the data acquisition devices on behalf of the FIA, and telemetry / communication systems to five teams.

The new regulations have been welcomed with a positive attitude. “We are sure,” states Roberto Dalla, in charge of motorsport at Magneti Marelli, “that whatever we are developing nowadays in terms of devices for F1 will be important components in new-age road cars. First of all, smaller and more efficient engines thanks to 500 bar direct injection (against 200-250 bar pressure in use on street cars), plus the turbo and ignition coils, parts of the combustion chamber, which work in optimal conditions.” Then there are MGU-K (KERS) and MGU-H, “which are both very interesting since they lead to the same power as that generated by the 2.4 litre V8’s with a 10-15% hike in terms of efficiency. Eventually this technology will find its way into road cars, starting with supercars that need to meet stricter emissions regulations.”

New technologies lead the way

Dalla’s excitement is contagious. He adds, “More than reducing the delay in turbo response, MGU-H allows for the recovery of a fair amount of energy from the exhaust gases. The new regulations allow this energy to be transferred directly to KERS instead of passing through the batteries – which will soon be totally discarded and substituted because of their weight and cost.” And the technological advancements aren’t restricted just to the electric motors, Dalla provides some more examples. The first is in regards to electronic brakeforce distribution “The brake-by-wire system takes into account the braking torque generated by the KERS system. Several street cars are equipped with similar, albeit less powerful braking systems.” Then there’s also Wi-Fi connectivity between the vehicle and the pits, which is able to work with latency periods of less than a tenth of a second. By connecting all the cars, a driver immediately knows if somebody spins out in a sharp turn just up the road. And if such technology could be made available in road cars, we could avoid bumping into the lorry parked across the street that’s scarcely visible. And there are still people who say F1 is of no use!

Immediate impact

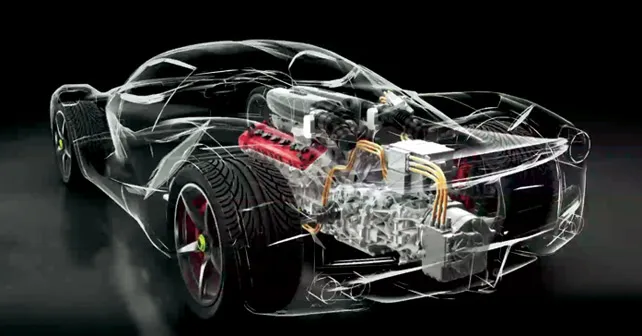

The first beneficiary is the hybrid ferrari

The LaFerrari can be considered one of the first examples that demonstrates the benefit of the work done in Formula 1 in regards to the development of KERS. The LaFerrari, which debuted at the Geneva Motor Show in 2013, is the first car from Maranello equipped with a hybrid system. The 6.3 litre V12 with 788hp has been combined with two electric motors and a series of batteries located in the floor. One of the electric motors is used to power the auxiliary systems, while the other has a power output of 163hp and is located at the end of the dual-clutch gearbox and helps the car achieve exceptional performance (such as acceleration from 0 to 200km/h in just 7 seconds). The total power is 948hp, but what’s more impressive is the total torque output of almost 900Nm. The batteries weigh in at just 60kgs, and supply instant torque until the petrol engine revs up to speed (it races all the way to 9,250rpm). This also ensures that CO2 emissions are kept low – at just 330g/km.

Shell case study

Even the petrol is bespoke

The research needed for the new F1 engines also involved oil & gas suppliers such as Shell – who work in close collaboration with Ferrari. “Our products that are used in the F14 T,” they explain “are completely new and constitute a combination of more than 50 mixes that have undergone a proper analysis in Maranello.” One of the most delicate aspects is the fact that the power units need to have a lifecycle double that of the previous V8’s. So, both oil and petrol need to guarantee better protection and reliability on all mechanical parts. Furthermore, the 100kg limit of petrol allowed during a race has led to an accelerated rate of development to achieve higher levels of efficiency. According to Shell, the petrol used by Ferrari contains 99% of the same components used by the commonly sold V-Power.

On the track

Each time an F1 Ferrari returns to the pits, the Shell engineers collect samples of the petrol and oil to analyse them at their lab in the paddock. During a race weekend, more than 70 tests are conducted on average

On the cars of the future

Sophisticated hybrid systems: the power units for 2014 are extremely rich in terms of innovations, which we will see on the cars of the future. Here’s a look at the Renault unit.

Mauro Forghieri

“The reduced noise levels in F1 may have been highly criticized, but this didn’t prevent the race in Bahrain from being one of the most exciting in the past decade”

Gian Paolo Dallara

“The ideal solution would be to recover kinetic energy under braking from the front axle as well. Nevertheless, we’ve already made significant progress”

© Riproduzione riservata

Write your Comment on