Carlos Ghosn's diabolical rebuttal against Nissan & the Japanese judicial system

The story of his escape will certainly go down in history as of one of the most daring escapes in the world, especially given the fact that we live in a world marked by surveillance and data control. And still, Ghosn was able to escape by hiring a group of American mercenaries.

Thanks to a diabolical plan worthy of a Bond movie, the former CEO of Renault-Nissan escaped from house arrest in Tokyo, took refuge in Beirut, and launched accusations against Nissan and the Japanese judges.

It wouldn’t be unfair to call him the Harvey Weinstein of the automotive world. But, unlike the disgraced Hollywood tycoon, Carlos Ghosn (pronounced ‘gone,’ funnily enough) decided against submitting to a trial and instead fled to a friendly country.

The Franco-Lebanon-Brazilian tycoon, who was once head of the world’s leading car manufacturer – the giant Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance – has, as everyone knows by now, escaped from Japan, where he was a prisoner, to Lebanon, where he has many political connections.

The story of his escape will certainly go down in history as of one of the most daring escapes in the world, especially given the fact that we live in a world marked by surveillance and data control. And still, Ghosn was able to escape by hiring a group of American mercenaries. The group comprised about 15 men who specialised in special operations and, more importantly, in hostage situations. To perfectly execute the plan, they prepared for weeks at a base in Dubai.

The plan began in December when a Tokyo court rejected Ghosn’s request to spend the holidays with his wife. So, the ‘Ghosnian’ special team got the green light, and the operation was a go.

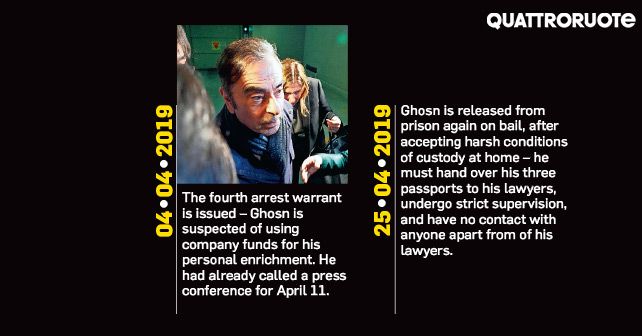

Around 2:30 pm, on December 29th, Ghosn left home – he could do so under the authorisation from the judiciary – and went to a hotel in Tokyo, the Grand Hyatt, where he rendezvoused with two men. From there, he proceeded to the train station and then boarded one of those superfast Japanese trains for Osaka.

In Osaka, he checked in a hotel near the airport. And he never left – well, at least not in the usual manner in which you would leave a hotel. So, how did he leave? Well, he got in a trunk, one of those big trunks made of aluminium and black plastic that are used to carry musical instruments for concerts – early on, some newspapers reported the use of a double bass case, which was an even more romantic hypothesis. The trunk was, then, taken to the airport of a neighboring city and loaded onto a private jet from Dubai. The jet is run by a company named Global Express – one of the biggest business jet companies in the world, which, then, left for Istanbul.

Osaka to Lebanon, via Istanbul

According to the Wall Street Journal’s reconstructions of events, once onboard the flight, Ghosn jumped out of his crate, but consciously remained in the blind spots of the pilots, who were unaware of the fact that there was a passenger on board as famous as he was problematic. At 5:12 in the morning, the plane landed in Istanbul, and Ghosn immediately boarded another smaller plane. Now, Global Express could easily have made a flight to Beirut directly from Osaka. So why stop in Istanbul, and unnecessarily delay the journey? Well, it was a carefully orchestrated ploy to avoid suspicion of Japanese authorities over a direct Osaka-Beirut flight.

Once he landed in the Lebanese capital, Ghosn was now free. He went directly to his Beirut residence, a building that – in a case of pure irony – was renovated at Nissan’s expense.

On January 8, Wednesday, in Beirut, Ghosn appeared donning a jacket, a tie, and his usual imperious air in front of hundreds of journalists from every country in a press conference, and declared that he wasn’t there to explain the details of his escape – too bad, for it would have provided great content for the scripting of a blockbuster Netflix series. ‘I’m here to explain why I escaped,’ he said, speaking with his usual modesty in the third person, showing court documents in giant slides, and alternating between English, Arabic, French, and Portuguese to answer different reporters.

He claimed that he gave life to a dying company, Nissan, and in return, he got a nice reward – prison! He bragged about ‘over twenty management manuals written about me,’ and then, above all, attacked the Japanese judicial system. ‘I fled not from justice, but from malice disguised as justice,’ he said.

The allegation on him, as is well known, is that he conspired to hide his expected retirement income of more than $140 million and, then, stole another $5 million from the company’s coffers. He, however, denies everything, considers the Japanese ungrateful, and also claims to be a victim of a judicial system that ‘violates the most basic principles of humanity.’ He also pointed out that he felt that he was being held ‘hostage’ – a clear reference to the system of hitojichi-shiho, otherwise known as ‘hostage justice,’ a peculiarity of Japanese justice, which keeps the accused in custody until they confess to the crime with which they’re accused.

‘They told me: you confess and everything will be all right. If you don’t, we won’t give you a break. Not only to you, but to your whole family,’ Ghosn said in a press conference, furious at the Japanese Minister of Justice, according to whom these are ‘intolerable’ accusations, which project ‘a false image of our system.’

However, it does seem that the Japanese justice system is tilted in favour of the accuser – this is attested by the fact that 99% of all cases result in convictions, and that the judges practically endorse the prosecutors’ demands. In the 1980s, recalls The Guardian, a top manager named Hiromasa Ezoe was accused of fraud and refused to confess. After ten years of trial, he was found innocent. In 2010, he wrote a book called Where is Justice? that describes the Japanese justice system as inhuman, wherein there is no trace of the presumption of innocence and the accused are almost automatically considered guilty. And if you’re a foreigner, it’s even worse. And even worse if you’re a famous manager – there are files ready in every case, ready to bring down anyone you need! Financial fraud, even those involving minimal amounts, are, then, punished with the utmost severity.

Not an ideal system for Ghosn then! You see, he has always been a bit of a braggart about his unregulated life, complained about his salary being too low (although he is a millionaire!), and has always given himself a much more bombastic image than the Japanese are used to.

Ghosn is also accused of organising a party in Paris in 2016 for his second wife’s 50th birthday. The ‘Marie Antoinette’ themed party, which had three-star chef Alain Ducasse cook for two hundred guests, was paid for, according to the prosecution, by Renault-Nissan, and it’s now being investigated by the French judiciary. Ghosn defends himself by saying that it’s a small matter and that Renault-Nissan was a sponsor of the palace... of Versailles.

Loved & Hated

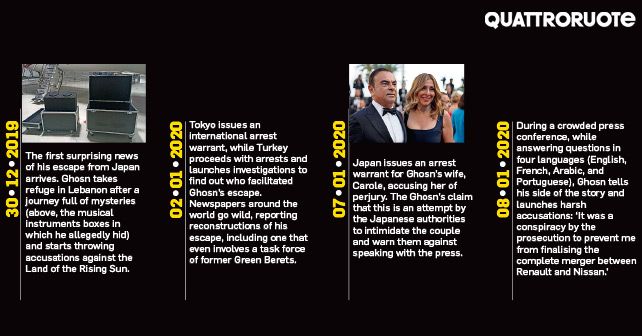

The mystery of the reality of Carlos Ghosn is something that still remains unsolved. In Beirut, he is a hero, while the Japanese consider him a fugitive. In France, there is a Ghosn Liberation Committee, and in Lebanon, where he grew up, he was immediately received by President Michel Aoun, with streets flooded with posters that read, ‘We are all Carlos Ghosn.’

Elsewhere, he got away with small fines. For instance, in the United States, where he paid $1 million to the American Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) in 2018 and was banned from working at a listed company for ten years. But Japan is not so flexible. At first, he was arrested and, then, was released on a total bail of $14 million. In 2019, Ghosn was imprisoned again, just after addressing a press conference in which he wanted to report his version of the facts.

A showdown that the Japanese could not tolerate, something which lies at the heart of what he believes is a real conspiracy worked out by ‘vindictive and unscrupulous individuals,’ who would have gone to any length to ensure that he was arrested, he claims. Here, he is referring to the top management of Nissan, who did not want Renault to gain too much power in the conglomerate with Nissan and Mitsubishi, and it was over this that Ghosn resigned.

Tale of a failed deal

In the press conference, Ghosn recalled the negotiations for a merger with FCA, which didn’t come to fruition because of his arrest. ‘In 2017, we were the group that produced the most cars and were preparing to add FCA to our portfolio,’ he said. ‘The deal was going to be finalized in January 2019, but I was arrested and everything fell apart. We missed a golden opportunity.’

Ghosn’s arrest led John Elkann to seek an alliance with the other French group – PSA – which was successful. ‘They said they turned the Ghosn page, because there is no plan and no growth. It was just a political case,’ said Ghosn.

In short, multiple developments in the automotive world revolved around this multi-faceted boss. Born in Brazil, the grandson of a Lebanese man who had made his fortune in South America, he moved to Lebanon – a land he considers home – at the age of six. ‘My name is Carlos Ghosn Bichara,’ he wrote in 2017 at the height of his glory. Bichara was his grandfather, his role model, who had emigrated from Lebanon to Brazil to make his fortune. In his many biographies, Ghosn never talks about his father, a mysterious figure who killed a man and went to jail for it – Georges Ghosn was apparently sentenced to death (although the sentence was never carried out) for the murder of a parish priest in a village north of Beirut, with whom he was dealing in diamonds. Amnestied for the murder in 1970, he was sent to the forger’s prison.

Cost Killer

A manager with four passports (French, Japanese, Lebanese, and Brazilian) and a globally successful déraciné, he was nicknamed the ‘cost killer’ at Michelin, where he worked in the 1990s after graduating in engineering from the prestigious École Polytechnique. At the age of sixteen, Ghosn moved to France. ‘You try to fit in because you’re different,’ he said years ago. ‘That’s what drives you to try to understand your environment. You tend to develop the ability to listen, to observe, to compare.’

At Michelin, he made a career, became the head of the American market. Then he joined Renault, and, in 1999, he arrived in Japan at Nissan, where he halved its debts in three years – cutting 21,000 jobs. He succeeded in an enterprise that was considered impossible by all, i.e., of putting together two groups numbed by the crisis and transforming them into a successful case history, while dismantling a key aspect of Japanese managerial culture, which included military-like loyalty, career advancements by seniority, and a lot of tradition.

He became CEO of both Nissan and Renault, a unique precedent, and a role that has always bothered Japanese shareholders, who were convinced that Paris exerted excessive influence. So, even his decision to resign from Nissan in 2017 was not enough – ‘I was ready to retire before June 2018. Unfortunately, I accepted the offer to continue to integrate the two companies. But some of my Japanese friends thought that the only way to get rid of Renault’s influence over Nissan was to get rid of me. I should have retired.’

Overall, a difficult character to categorise – one who has always kept a fallback ready in Lebanon, just in case, not to mention someone with the ability to contact and recruit a team of mercenaries for what was essentially a war-like operation. ‘I’m used to missions impossible,’ he joked with journalists. But ‘he’s not a terrorist,’ said his daughter Caroline to the New York Times on the eve of the escape, when the family was about to be reunited for Christmas. But the magistrate, in Japan, had re-arrested Ghosn, thus compelling him to play his final card of escape.

In the fall, his lawyers had explained to him that his case would last at least five years – ‘a violation of the right to fair trial time,’ according to him. And the rest is well known by now – a hired team of former military personnel studied the best (i.e. the worst) airports between Tokyo and Osaka, those with fewer controls and where a trunk big enough to hold Ghosn wouldn’t have to go through metal detectors. From Dubai to Tokyo and Osaka, they made various trips in preparation for the mission, which had only one chance of success. The day before the escape, on December 29th, Ghosn dined at his favourite restaurant in Tokyo – a nice picture was taken with the waiters – and went to sleep.

Now, he’s in Beirut, in a kind of golden exile, where he knows that he’s practically untouchable. Lebanon has no extradition agreements with Japan, where he is impatiently awaited (with, probably, a desire for revenge). He has said that ‘he’s ready to stand trial, where it will be a fair trial.’

Apparently, in his future, a return to Tokyo seems unlikely. So, for the moment, the big fugitive hunt is still on.

The building in Beirut, in which the former Renault-Nissan boss took refuge, protected by security.

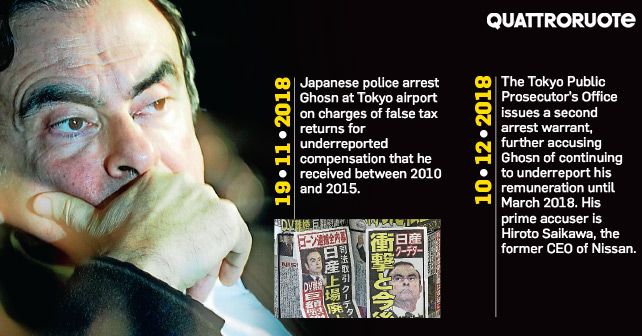

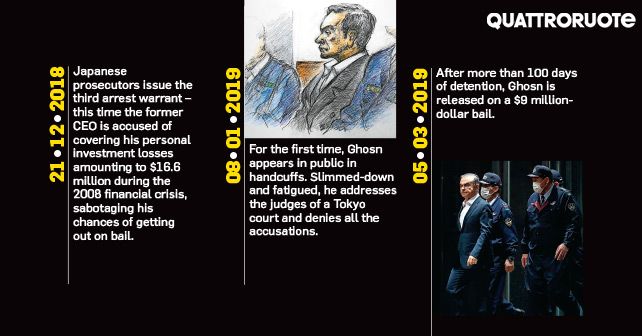

The Stages of The Soap Opera

An Alliance in Perennial Crisis

The Renault-Nissan story is one that’s been repeated a thousand times throughout history – that of a political creation not outliving its creator. At the end of the Ghosn era, the centrifugal tendencies of Japan immediately emerged. The interference of Paris has never sat well with Japan, not even when, two years after the settlement, the cosmopolitan manager had brought Nissan back into the black. And the reason is very simple – when, in 2001, the cross-shareholding deal was sealed (the French got 44.4% of Nissan, while the Japanese got 15% of Renault), the Japanese were given their shares without voting rights. The Japanese saw it as a grossly unjust deal, towards which they became increasingly intolerable as Nissan’s financial performance became stronger (unlike that of Renault). Meanwhile, the French government was looking to increase its share in Renault. When, in 2015, Emmanuel Macron, then the Minister of the Economy, temporarily increased the State’s share in Renault to 19.7%, Hiroto Saikawa of Nissan threatened to blow up the Alliance. An idea revisited in mid-January 2020, when the Financial Times revealed the existence of a Japanese plan for a future without Renault. However, such a possibility was denied by both companies. Needless to say, the future of the Alliance is very much in question as it stands today.

In October, Makoto Uchida replaced Hiroto Saikwa as the president and CEO of Nissan. The latter left after he was accused of being overpaid. Uchida is at the top of a triumvirate that also includes Ashwani Gupta and Hideyuki Sakamoto.

$15 Billion Burned

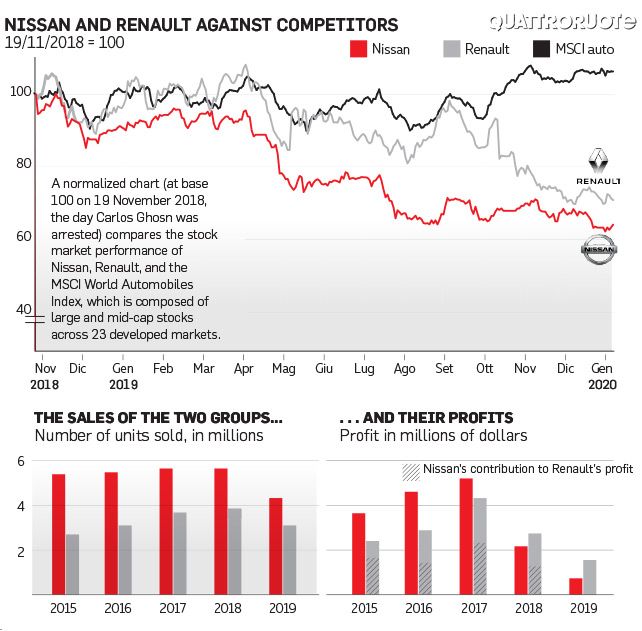

‘Since my arrest, Nissan’s capitalisation has dropped by $10 billion and Renault’s by almost $5 billion. They said they’ve moved on, and it’s true because there’s no plan and no growth now.’ During the press conference, Carlos Ghosn also remarked on the steep decline the two companies suffered at the stock market. And, in fact, since November 19, 2018, Renault has lost about 30% and Nissan over 40% of their respective valuations, while, in the same period, the auto sector stocks (according to the global MSCI index) have gained just under 10%.

The Turn to an Italian

Two CEOs’ depart within a year (Thierry Bolloré of Renault and Hiroto Saikawa of Nissan), declining sales with decreasing margins (see the graphs on the opposite page), the first line of managers on the run, increasingly complicated governance, and the technical collaboration at an all-time low within the Alliance. It’s certainly not an easy skin to untangle for Luca De Meo, the now-former CEO of Seat and the only candidate for the role of CEO of Renault, which is recovering from the Ghosn scandal, the failure of the negotiations with FCA, and a phase that has proved dramatic and debilitating. The challenge for the manager, born in 1967, who returns today as a boss to his first company, is tough but certainly stimulating. The first, and most urgent, objective is the recovery of sales and profitability – in the first 11 months of 2019, the alliance registered about 500,000 vehicles less than what it did in the same period of 2018. ‘Our performance is poor and disappointing. And we can’t go on like this,’ said chairman Dominique Senard, hence the need to turn to and rely on De Meo’s experience and capabilities.

© Riproduzione riservata

Also read - Collaboration is the key for survival of the auto industry

.webp)

Write your Comment on