Farewell, Frank...

The death of Sir Frank Williams is a sad moment in the Formula 1 world. It’s hard to even begin to try to quantify the impact that Frank Williams had on the Formula 1 team that bears his name – and on the sport itself.

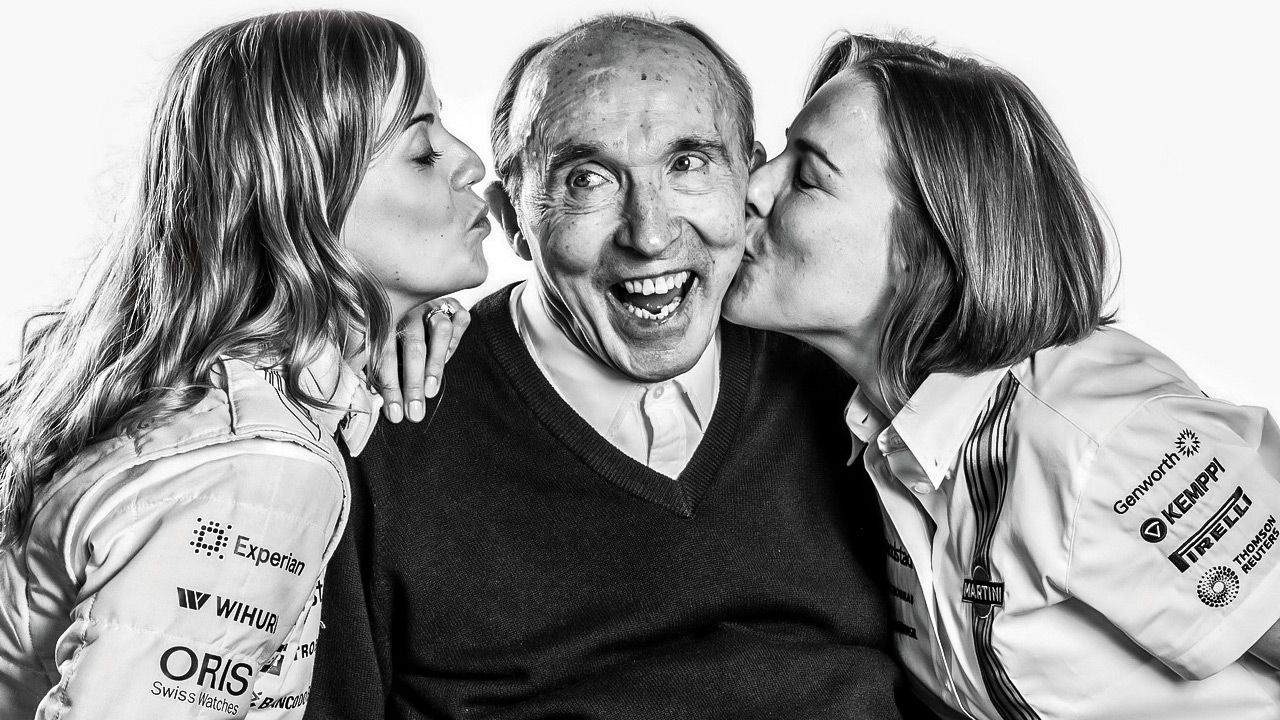

Joe bids Sir Francis farewell.

The death of Sir Frank Williams is a sad moment in the Formula 1 world.

It’s hard to even begin to try to quantify the impact that Frank Williams had on the Formula 1 team that bears his name – and on the sport itself.

FW, or Francis, as he was known to some of us, died at the end of November, at the age of 79. In recent months, he had come close to death on a number of occasions. In the end, while his fighting spirit remained, his body finally gave out.

A gritty, determined, charismatic and funny man, Frank built his success on learning from failure. And then, when he was riding a high, during the successful years of the Williams-Honda relationship, he had a road accident that he admitted was entirely his own fault. This left him tetraplegic, which meant that he had limited use of his upper arms but nothing else. He was confined to a wheelchair, in need of constant nursing, but if he had moments when he felt sorry for himself, they did not last long. His view was that he had got himself into that predicament, and so he had to adapt to it. He embarked on what he called ‘a different kind of life,’ and with the support of his wife Ginny, and the dogged brilliance of his business partner Patrick Head, Francis led the team to even greater success in the early 1990s.

Williams was a Geordie (from the North East of England), although he could turn the accent on and off. Born in South Shields, the son of a Royal Air Force officer and a schoolteacher, who later became a headmistress. The family broke up when he was still young and he spent some of his childhood living with his mother’s sister before being sent away to boarding school at St Joseph’s College in Dumfries, Scotland. This was a private catholic school and it gave FW a distaste for religion and a passion for cars, or, more specifically, racing cars.

He left school at 17, intent on becoming a racing driver and did a variety of jobs while hitchhiking to races all over the country from Nottingham – where he then lived with his mother. He raised the money required to buy a clapped-out Austin A35, rebuilt it and then wrecked it against a lamppost in Salisbury. He bought another and destroyed it in a crash at Mallory Park. His racing adventures meant that he got into the racing crowd – peopled largely by wealthy young men – and Frank began making his way with these new pals, working as a mechanic with his namesake Jonathan Williams, travelling to Formula Junior races all across Europe. Frank learned languages and made connections. He would often stay at a flat in Harrow, where a group of young racers were based – among them Piers Courage and Charlie Crichton-Stuart. He raced when he could, but mainly built a business buying and selling racing parts. This meant that, eventually, he founded Frank Williams Racing Cars in rented premises in Slough and began entering cars for Courage – the heir to the famous brewing family. They ran in Formula 2 in 1968, and a year later bought an ex-factory Brabham Formula 1 car and entered it in selected races for Courage. The team scored two second-places that year. His Italian connections opened the way for a deal to run a de Tomaso F1 car, funded by the car company and designed by Giampaolo Dallara. Sadly, Courage crashed and was killed at Zandvoort that summer, an accident that hardened Williams.

For the next seven years, he ran cars under different names – there was the Politoys FX3 and then the Iso-Marlboros, but he was constantly on the verge of bankruptcy. He became known as ‘Wanker Williams,’ because of his lack of success. In the end, he was forced to sell the team to Canadian oil magnate Walter Wolf in 1976. When Wolf dropped him from the race team at the start of 1977, Frank departed and set up a new team in league with engineer Patrick Head. They set up shop in an old carpet warehouse in Didcot and acquired an old March F1 car, which was driven by Patrick Neve, who had funding from the Belgian Belle-Vue brewery. And, thus, a legend was born – tempered by the previous failure and driven by passion and ambition. Williams Grand Prix Engineering won sixteen World Championships between 1980 and 2007, with 114 Grand Prix victories. Along the way, the team designed and built the Austin Rover Metro 6R4 Group B rally car, entered and won the British Touring Car Championship with Renault and Alain Menu, joined forces with BMW to design and build the BMW V12 LMR, which won Le Mans in 1999 in the hands of Yannick Dalmas, Pierluigi Martini and Joachim Winkelhock.

After winning World Championships with Honda and Renault, Williams came close again with BMW in 2003. But then BMW decided to move on and do their own thing, and Williams was left with customer engines. Relationships with Cosworth, Toyota and Renault followed without success – except for one incongruous, but wonderful, victory – the team’s 114th – in Spain in 2012, when Pastor Maldonado drove like a legend. Frank was celebrating his 70th birthday and his wife Ginny, already ill with cancer, was present for what would be her last visit to an F1 race.

Frank never really got over Ginny’s death, early in 2013. They had been together for more than 40 years, through thick and thin, and he struggled to cope without her. Even before that there had been signs of mental deterioration. Frank would forget conversations that he had just had, although his memories of the old days remained clear. Frank had been looking for someone to replace him as the team leader from as early as 2005 when he picked Chris Chapple to be CEO – who would be replaced by Adam Parr and then Toto Wolff, but Toto subsequently got an offer to join Mercedes and left Williams. In the end, Frank’s daughter Claire took the role, but this was not a success, and by the middle of 2020 the team was in serious danger of collapsing and was sold to the investment firm Dorilton.

Motor racing made him a wealthy man, and his achievements were recognised in many different ways – with his appointment as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) back in 1987. He was also appointed a chevalier in France’s Légion d’Honneur, in recognition of his achievements with Renault engines, and in 1999 he was knighted in the UK.

FW was the force that made the team a success, with Patrick translating those ambitions into reality, but when people talk of ‘Frank and Patrick’ they ought really to say ‘Frank, Patrick and Ginny,’ as she was a very real force, as Frank’s partner and closest advisor.

Joe Saward has been covering Formula 1 full-time for over 30 years. He has not missed a race since 1988.

Read more:

.webp)

.webp)

Write your Comment on