The mating of an accelerated development schedule with the will to create history, led to a truly historic achievement at this year’s Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

The mating of an accelerated development schedule with the will to create history, led to a truly historic achievement at this year’s Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

This wasn’t the first time in the 96 editions of the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb since 1916 that a driver in an electric car was faster than all the other entrants. Back in 2015 – just two years after former nine-time world rally champion Sebastien Loeb had set what looked like an unbeatable overall record of 8m13.578sec on the 156 turn, 19.99km course in Colorado, USA – Rhys Millen made history by beating even the internal combustion engine cars.

However, Volkswagen Motorsport’s overall victory and the time set by former FIA World Endurance Champion, 24 Hours of Le Mans winner and now four-time event winner Romain Dumas of 7m57.148sec in the revolutionary and visually striking all-electric I.D. R Pikes Peak, made even those who don’t normally follow the world of automobiles and motorsport sit up and take notice.

Loeb’s sensational time on the course, where the start line is at 2,862 metres above sea level and the finish at 4,301 metres at the summit of ‘America’s Mountain’ was expected to stand for a very long time and most certainly not threatened by an electric car.

Especially as the previous electric car record of 8m57.118sec (again set by Rhys Millen) was a long way off. When Millen set that time in 2016, he finished second to Dumas, who was driving a petrol engine-powered prototype sports car that competes in the FIA European Hill Climb Championship (which was ironically driven by the driver who finished second to him this year).

Weapon Of Choice

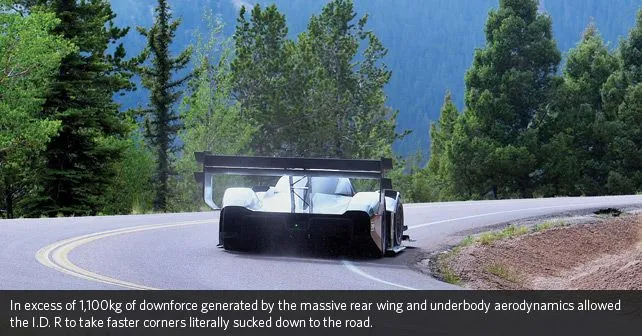

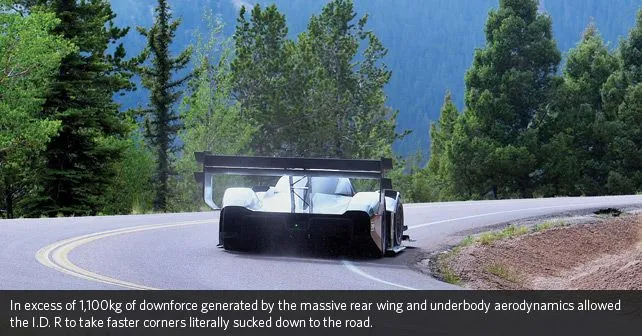

This April, just two months prior to the hill climb and after an eight month development period, Volkswagen Motorsport debuted the I.D. R Pikes Peak. Essentially a closed-cockpit prototype sportscar but built specifically for Pikes Peak. It’s massive rear wing plus underbody aerodynamics produced more downforce than the 1,100kg kerb weight of the car.

Testing followed on both a regular race-track as well as at Pikes Peak. Dumas was drafted to chase his fourth win at the event, secure Volkswagen’s first overall win and also the electric car record. Former German rally champion Dieter Depping’s inputs throughout the development period were essential too, allowing Dumas to focus mostly on fine tuning the 671bhp, 650nm car to his driving preferences.

Qualifying for the event had started, as I and the rest of the 90 odd journalists that VW had invited to cover their attempt touched down in Denver International Airport to hit the road to Colorado Springs, which was 135km away to the south.

Qualifying, held over a 3.17km section of the course, decided the start order on race day. On race-day, cars would make their solitary runs in order of the fastest to the slowest qualifier after the motorcycles had run in order of the slowest to the fastest. In 2013, during his record-breaking run, Loeb had topped qualifying with a time of 3m26.728sec. In second place that year was Dumas, 23 seconds behind.

Fast-forward to the present day, and Dumas’s qualifying time in the I.D. R was 3m16.083sec. Loeb may not have been able to defend his record even if he had taken part in this year’s event!

Suddenly, it became clear that VW Motorsport were fooling no one when they said they were only after the electric car record.

During the final practice session – at 3,984 metres above sea level and not far from the finish line at the summit of Pikes Peak – it became apparent that if nothing else, no vehicle could match the I.D. R’s insane acceleration. With the instantaneous torque (the advantages of electric power) from its two electric motors that run the axles, Volkswagen Motorsport’s claimed time of 2.25 seconds to reach 100km/h (faster than even a Formula 1 car) appeared accurate.

And since this was an electric car, the rise in altitude would not lead to a loss in power. Internal combustion engine cars would lose 29 percent of their maximum power at the Pikes Peak start line and 43 percent at the finish on the summit.

The all-wheel drive channelled through wide slick tyres not only helped the car shoot off like a rocket but to corner like it was on rails.

Standing 3.2km from the start at Engineer’s corner on race-day, notorious for crashes by those who saw it too late, I could clearly see how the I.D. R wiped off speed coming into the braking zone for a tight left-handed hairpin, and then shot right out of it again for a fast and uphill right-handed corner that took it to a short straight before tackling the remaining twists and turns. The I.D. R got to the spot I was standing at in around a minute and ten seconds!

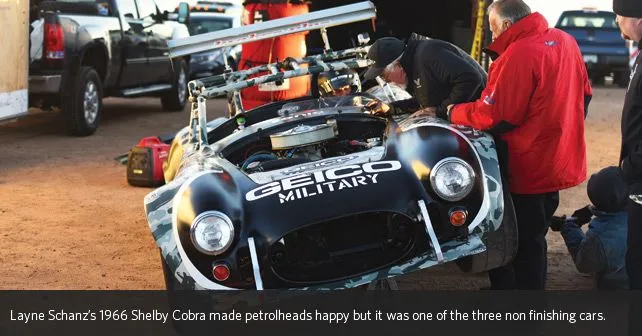

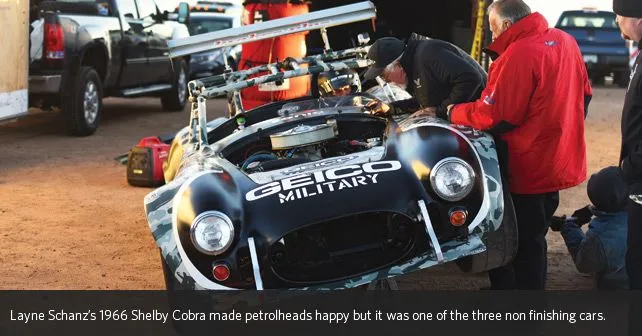

Both at Devil’s Playground during practice and at Engineer’s on race day, the speed of the vehicle was very much apparent, even without the audio aid of the traditional scream/growl/roar/backfire of an internal combustion engine. The fastest example of which was Pikes Peak rookie, and multiple European hill climb champion, Simone Faggioli’s Norma prototype that was second overall with a time of 8m37.230sec.

That is a highly impressive time, as it equated to an average speed of 134.38km/h over the course of his run (Dumas averaged 145.7km/h). It was just over 24 seconds slower than Loeb’s previous record, which came after a massive factory effort and, of course, with Loeb driving. Loeb apparently would do his practice runs and then be driven down blindfolded, as he did not want to even accidentally visualize the course in a downhill configuration.

What made Faggioli’s run even more impressive was that he drove a rear-wheel-drive car (unlike both Loeb and Dumas) that had neither a Pikes Peak-spec rear-wing or underbody aerodynamics as the car normally runs on roads in Europe that are far bumpier as compared to the smooth surface in Colorado.

Real World Issues

The event, founded in 1916 by Spencer Penrose as a way to attract tourists to his hotel (The Broadmoor) and to the city of Colorado Springs used to be held on an entirely gravel surface until 1994, after which a local environmental body brought up an issue of that same gravel entering the water supply of Colorado Springs. This led to the paving of the course at a cost of 1 million US dollars per mile (or `6.8 crore per 1.6 km).

Despite incurring that heavy financial burden, the event staved off closure on account of its fame in American motorsport, thanks to the exploits of that country’s ‘racing royalty’ like the Unser family whose members won multiple times.

And from the mid-1980s, it had garnered global popularity because of the record-breaking campaigns by brands like Audi and Peugeot, whose Group B rally cars (deemed unsafe to race in the World Rally Championship) were driven by their star drivers like Michelle Mouton, Walter Rohrl and, of course, Ari Vatanen, whose record-breaking 1988 run in a Peugeot 405 T16 has been immortalized by the short film, ‘Climb Dance’.

As has Rod Millen’s record run in 1994 of 10m04.06sec in an all-wheel drive Toyota Celica. It was the last time the overall record was set when the course was all gravel. It took Japan’s Nobuhiro ‘Monster’ Tajima 13 years to break that record in his Suzuki XL7 Hill Climb Special, but by that time the course was partially paved.

Now in the full-tarmac era, Volkswagen’s attention-grabbing achievement will do no harm to both the cause of all-electric vehicles, as well as its reputation in America, which took a massive hit on account of ‘Dieselgate’.

Volkswagen has already announced electric car models that will follow the I.D. nomenclature and will feature the same technology as found on the I.D. R. Thereby fulfilling a very important role of motorsport in being the ultimate laboratory and proving ground for automotive technology and research.

Write your Comment on